Overview

In August 2025, Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen from Stanford Digital Economy Lab published what I consider one of the most insightful papers on the future of work in the AI Age. In their 57-page report called “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence,” they achieve several unique things. [1]

- First and foremost, they rely on actual data regarding people’s salaries: “This study uses data from ADP, the largest payroll processing firm in America. The company provides payroll services for firms employing over 25 million workers in the US. We use this information to track employment changes for workers in occupations measured as more or less exposed to artificial intelligence.”

- Secondly, they also cite “Occupational AI Exposure” (mainly based on the work of Eloundou et al., 2024) and the Anthropic Economic Index (Handa et al., 2025). They use this information to “estimate whether the use of AI for an occupation is mainly complementary or substitutable with labor.” This is how they link professions like “software developers” and “Customer Service” to AI usage.

- Thirdly, to provide context, they calibrate their data by comparing “teleworkable” and “non-teleworkable” occupations, as well as the “Personal Consumption Expenditure index.”

I mention this robust research method because there is a lot of writing on “AI and society” that is hype, opinion, and just bad fake science (see MIT research on “95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing” [2]. Caveat emptor (buyer beware).

To Be a Canary in the AI First Workplace

For centuries, coal miners brought small canaries into the mines. These birds were much more sensitive to toxic gases like carbon monoxide and methane than humans. If the canary became ill or died, it served as an early warning that conditions were unsafe, giving miners time to evacuate.

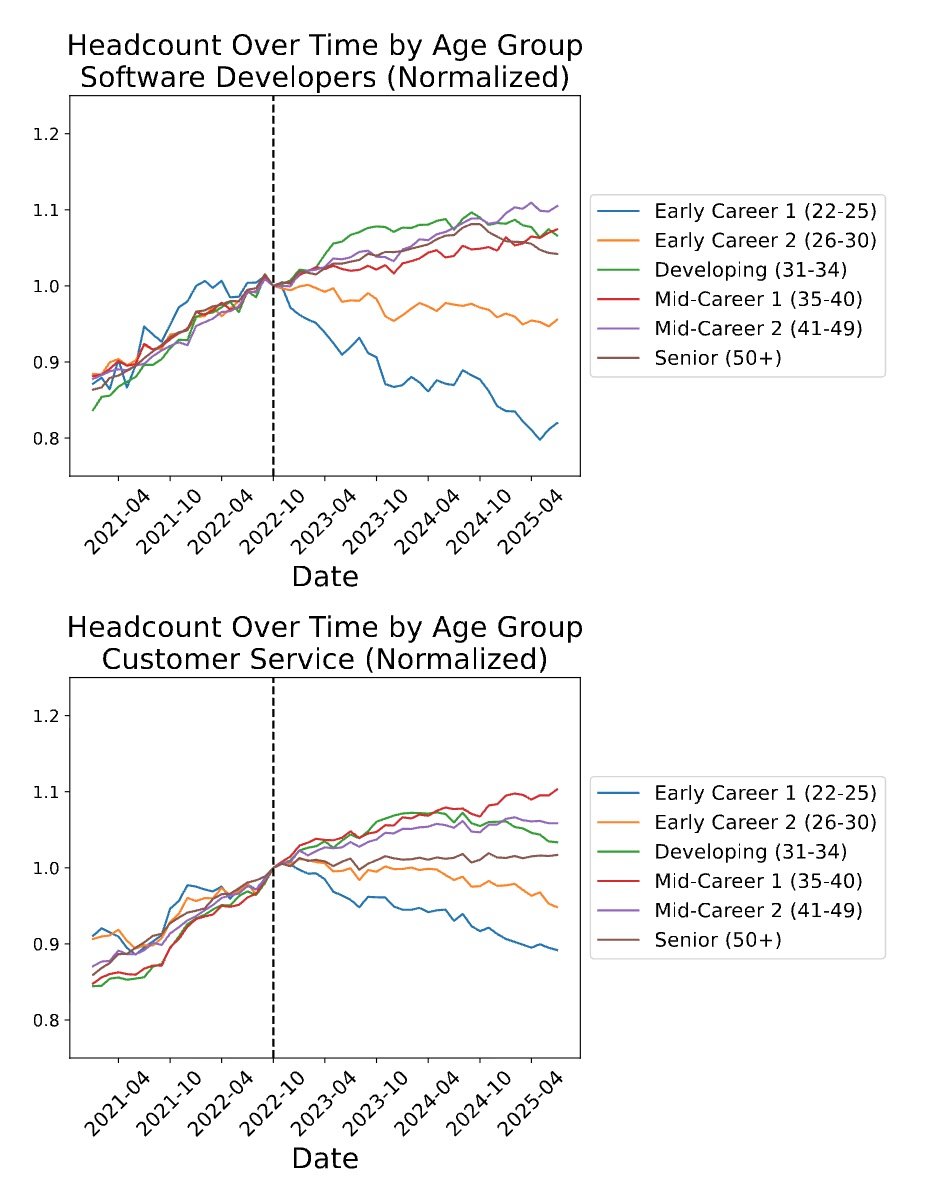

By analogy, we can see from this paper that AI is influencing professions with high AI exposure. Specifically, the authors show the impact of AI on two professions: Software Developers and Customer Service—two fields with significant, direct effects (although different in nature, and I will share my reflections on this later).

Both professions show the same pattern: a roughly 20% decline in headcount from October 2022 (local peak) to July 2025.

Key Results

As Visual 2 suggests, there is a clear difference in the headcount number by age. Younger people have fewer options.

The visual “shows employment changes by age group for these occupations, normalized to 1 in October 2022. Both occupations present a similar pattern: employment for the youngest workers declines considerably after 2022, while employment for other age groups continues to grow. By July 2025, employment for software developers aged 22-25 declined by nearly 20% compared to its peak in late 2022.״

The canary is getting sicker in this case.

Impact of Software Developers

The top profession impacted by AI is software development. Programming (once again) is no longer what it used to be. I have firsthand experience with this—as I programmed in Z-80 Assembly and also used “call -151” on the Apple IIe. Programming seems to evolve every decade: we used to read books (my most loved book, UCSD Pascal Guide), save work on floppy disks, adopt object-oriented paradigms, and later rely too heavily on Stack Overflow. There are many new concepts, metaphors, and methods. What we have now is yet another shift, though it’s a major one.

For techies: telling an agent ‘do this,’ then watching it create the PR, pass tests, merge into code, and auto-deploy via CI/CD — that experience is simply amazing.

All professionals get ready: software is 5 years ahead of your profession because it has the perfect storm. A small set of rules (programming languages),the ability to self-test, users (=developers)who love efficiencies, and apparent outcomes (real programs that run). “More than a quarter of all new code at Google is generated by AI, then reviewed and accepted by engineers.” — Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, during the company’s Q3 2024 earnings call.

Who pays the price? junior positions.

Companies are hesitant to hire individuals who may not fully grasp the capabilities of AI. Senior people, and good ones, are much better. A single senior with AI is equal to a team of 4. Why bother the senior with fixing the hallucinated PRs of juniors? Good developers used to be 10 times better than the average; now they are 20 times more effective. Why hire padawans? When can you get the real AI-powered Jedi Knights?

Impact on Service

Service is also an intriguing story. On one hand, AI can now “digitize” most well-defined scenarios and manage most cases, enabling humans to concentrate on the “difficult/interesting/unique/high value” cases.

But here is my take. This is just the start. Service will slowly be minimized. Products will increasingly fix themselves, provide on-the-spot help, and reduce or even eliminate the need for user service. Things should work. (Consider Tesla service—so different from the traditional garage. The product has changed, and with it, its service model.)

Other Results From the Paper (Summed by Gemini)

- Disproportionate Impact on Early-Career Workers: Since the widespread adoption of generative AI, early-career workers (ages 22-25) in the most AI-exposed occupations have seen a notable drop in employment. Meanwhile, employment for more experienced workers in the same fields has stayed stable or continued to grow.

- Concentration in Specific Occupations: Employment declines are most noticeable in jobs where AI is more likely to automate than assist human workers. Examples of these roles include software developers and customer service representatives.

- Employment vs. Compensation: The study found that labor market adjustments are mainly happening through employment rather than changes in compensation. This suggests that instead of wages being cut, people are losing their jobs.

- Strong Overall Employment Growth: Despite declines among young workers in AI-related fields, overall employment in the American labor market continues to grow strongly. This suggests a redistribution of jobs rather than a complete loss of employment.

- Tacit Knowledge acts as a Buffer: Older workers, who have gained “tacit knowledge” or unwritten practical skills through experience, are less likely to be replaced by AI. This type of knowledge is not easily duplicated by large language models.

- AI as a “Canary in the Coal Mine”: The paper uses the metaphor of “canaries in the coal mine” to describe early-career workers in jobs exposed to AI. Their disproportionate job losses could serve as an early warning sign of AI’s broader and more disruptive impact on the workforce.

My Take

I believe AI is the first technology to eliminate more jobs than it creates. This has NEVER happened before; all previous technologies created more jobs. At MindLi, we are working hard to support human thinking as AI develops, making sure AI becomes a net positive for people.

More Information:

- [1] Full paper: Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence (PDF): https://digitaleconomy.stanford.edu/publications/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/

- [2] Reference to the Fortune article (based on an MIT report) claiming that “95 percent of generative AI pilots fail”: https://fortune.com/2025/08/18/mit-report-95-percent-generative-ai-pilots-at-companies-failing-cfo/

AI Tools Used

- Main writing — ChaptGPT Canvas.

- Image — Google Gemini (zero shot, just had to make the people scared — because in the first version, they were all smiling, not sure why)

- Summary of key points — Gemini took directly from URL.

- Final editing. Grammarly.

- Crazy AI things: I wrote, “I believe AI is the first technology to kill more jobs than it creates.” AI fixed this to “I believe AI is the first technology to create more jobs than it eliminates”.